Cambodia: Chut Wutty’s legacy creates an opportunity for land justice

Activist’s murder in 2012 and election blow to Hun Sen’s government could trigger political change, say campaigners

In Cambodia, there is talk of change. Not just from Hun Sen, the prime minister, who has promised reforms after his party suffered a significant blow in recent elections, but from environmental activists and campaigners, who say there has never before been such an opportunity to lobby a government that has long ruled with an iron fist.

Despite alleged illegal logging, land grabs, harassment and threats by police and government thugs, activists claim the ruling party’s win in July of just 68 seats to the opposition’s 55 means that Hun Sen, who has governed Cambodia for the past 28 years, may be softening, out of necessity, to the will of the people, in turn allowing environmental groups to gain strategic ground.

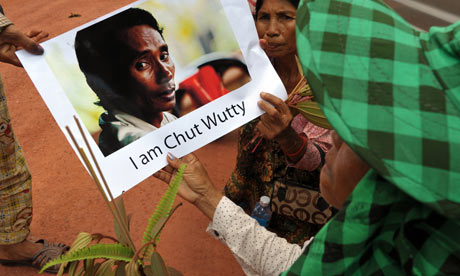

This is due, in part, to the increasing awareness of human rights and social justice issues, activists say, such as the death of one of Cambodia’s most prominent environmental activists, Chut Wutty, in April 2012. He was investigating illegal logging and land seizures with two journalists when he was shot dead by Cambodian military police officers.

Though a provincial court dropped charges against his alleged murderer and the government failed to conduct an adequate investigation, Wutty’s death has resonated far beyond Cambodia. Last week, the activist wasposthumously awarded in London for “extraordinary achievement in environmental and human rights activism” by the Alexander Soros Foundation, which promotes global social justice. The accolade was accepted on his behalf by the Prey Lang Community Network (PLCN), which is campaigning to protect the largest remaining primary forest in mainland south-east Asia.

“The cause Wutty died fighting for has never been more important or more deadly,” Soros said. “Cambodian activists and citizens remain on the front line of the country’s land-grabbing crisis, as Cambodia’s elites sell off community land and forests without their consent.”

In Cambodia, the award was welcomed by local campaigners, who say it proves “[Wutty’s] death is not forgotten”. “Community networks are more advanced now,” said conservationist Marcus Hardtke, a close friend of Wutty’s who has lived in Cambodia for the past 17 years.

“Wutty was pretty instrumental in starting this [method of] community law enforcement because, until then, the communities couldn’t rely on the uniforms and officials [who] were either not interested [in their cause] or supporting the other side, big businesses, so they had to protect themselves. This [award] sends a strong signal to the government and to activists that his death is not forgotten – it’s going forward.”

Wutty’s death has arguably been the highest-profile murder in Cambodia, where activists routinely face harassment and threats while campaigning for land justice. Not long after Wutty’s death, a 14-year-old girl was killed by military police during a land dispute and, later, a journalist investigating timber companies was discovered dead in a car boot.

A report into the number of deaths arising from land and forest disputes worldwide, published in June 2012 by the activist group Global Witness(pdf), found that two people were killed a week in 2011 – nearly twice the number recorded in 2009.

It stated that in Cambodia there was “strong evidence that the killings were perpetrated with company or government involvement”. According to the human rights group Licadho, 2012 was “the most violent year ever [for Cambodians] … in terms of the authorities using lethal force against activists”, with 232 arrests recorded – a 144% increase from 2011, according to Adhoc, a local NGO.

Land rights were, perhaps unsurprisingly, a huge talking point during this year’s election. More than 2m hectares of land – equivalent to nearly three-quarters of Cambodia’s arable land – have been granted to investors since 2008, in turn affecting an estimated 700,000 people across the country, according to Global Witness.

Protesters have been vocal and their complaints taken on by the opposition Cambodian National Rescue party (CNRP), which has called for an end to all concessions and greater land justice.

This may explain why Hun Sen issued a full moratorium on economic land concessions (ELCs) in May 2012, yet inserted a key loophole that allowed those already approved, but not yet started, to move ahead. The result was that nearly 400,000 hectares of land were granted as concessions last year, nearly three-quarters of which came from wildlife sanctuaries and protected forest.

The CNRP is boycotting parliament in an effort to lobby Hun Sen’s government for reform, including calls for an independent inquiry into alleged voting irregularities and an end to land, mining and forestry concessions.

Though the leader’s call last month for a full moratorium on ELCs and an inquiry into those being processed was met with scepticism by activists and analysts, campaigners say Cambodia’s current unprecedented political landscape may allow them to “gain strategic ground” in lobbying for change.

“If we don’t focus on saving our forests [now], this will be the last chance we have to save them,” said activist Seng Sokheng, of the Community Peace-Building Network, which works closely with the PLCN. “We are all speaking up to protect the forests and prevent illegal logging, all around the country now, and I do believe that the government will listen.”